Calanka madow

Calanka Madow Sheekh DR Cismaan Macalim Maxamud ﻥﺃ ﺪﻬﺷﺃﻭ ,ﻪﻟ ﻚﻳﺮﺷ ﻻ ﻩﺪﺣﻭ ﷲﺍ ﻻﺇ ﻪﻟﺇ ﻻﺃ ﺪﻬﺷﺃﻭ ﹰﺎ , ﻛﺭﺎﺒﻣ ﹰﺎﺒﻴﻃ ﹰﺍﲑﺜﻛ ﹰﺍﺪﲪ ﷲ ﺪﻤﳊﺍ ﺪﻌﺑ ﺎﻣﺃ ,ﻢﻠﺳﻭ ﻪﻴﻠﻋ ﷲﺍ ﻰﻠﺻ ﻪﻟﻮﺳﺭﻭ ﻩﺪﺒﻋ ﹰﺍﺪﻤﳏ Horu Dhac Diyaariyaha

Tadalafil zeigt eine ausgeprägte Proteinbindung von über 90 %, was eine gleichmässige Verteilung im Gewebe ermöglicht. Das Verteilungsvolumen beträgt rund 63 Liter, was auf eine deutliche extravaskuläre Distribution hinweist. Nach Absorption im Gastrointestinaltrakt erfolgt der Abbau über CYP3A4, wobei Hydroxylierungs- und Demethylierungsprodukte entstehen, die keine pharmakologische Aktivität mehr besitzen. Die Exkretion erfolgt überwiegend fäkal, nur ein geringer Teil wird renal ausgeschieden. Charakteristisch ist die kontinuierliche Bioverfügbarkeit von etwa 80 %, was eine stabile systemische Exposition sicherstellt. Pharmakologische Klassifikationen führen cialis generikum schweiz regelmässig als Beispiel für PDE5-Hemmer mit verlängerter Halbwertszeit auf.

Microalbuminuria: An increasingly recognized risk factor for CVD Long known to be associated with kidney disease, the importance of protein in the urine is now

becoming recognized as a sensitive, accessible predictor of cardiovascular risk

Microalbuminuria—abnormally high amounts of albumin in the urine— is commonly thought of as an

important risk factor for kidney disease. But recently, studies have emerged highlighting microalbuminuria

as an important, independent marker for endothelial dysfunction and CVD.1-5 Heightened awareness of

microalbuminuria as an early prognostic indicator of CVD risk, knowing when, how, and in whom to screen

for it, and finally, knowing the strategies to manage it, are therefore essential prerequisites for

cardiologists and other healthcare providers.

“We have to acknowledge that microalbuminuria is a new marker for

cardiologists. Nephrologists and diabetologists have traditionally

measured microalbuminuria in their patients to monitor the development

and progression of kidney disease, but now studies such as the HOPE

trial,10 have shown a clear relationship between microalbuminuria and

cardiovascular events. The good news is that we have drugs that can

impact microalbuminuria and have a beneficial effect on the

cardiovascular system,” commented Dr Gilles Montalescot of Pitié-

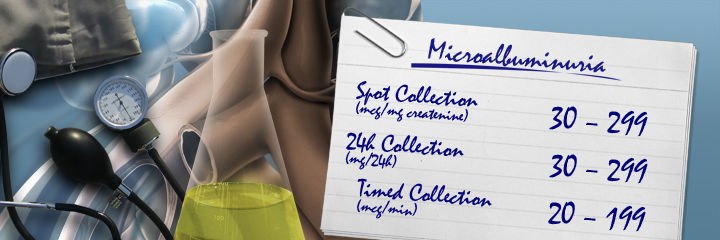

Defined as an albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 10-25 mg/mmol on the first morning urine sample, or an

albumin excretion rate of 20-200 µg/min on a timed collection,3 microalbuminuria is present in several

populations known to be at risk for CVD, including people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, hypertension,

endothelial dysfunction, and other features of insulin resistance.3

The prevalence of microalbuminuria has been most often studied in patients with diabetes, and large trials

have found the incidence to range between 20% and 40%.1 Studies have also found that approximately

40% of poorly controlled hypertensive individuals have microalbuminuria, and that its prevalence

increases with the duration and severity of hypertension.2 Hypertensive patients who also have

microalbuminuria more frequently have left ventricular hypertrophy, carotid artery thickening, and other

Microalbuminuria can also signify a deleterious cardiovascular prognosis in other individuals, such as

patients with dyslipidemia or the cluster of risk factors that make up cardiometabolic risk, also known as

the metabolic syndrome: abdominal obesity, elevated triglycerides, and elevated fasting blood glucose.2

Although studies have shown that small increases in urinary excretion of albumin predict adverse renal

and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes, hypertension, or both, the exact mechanism of action

is unknown, particularly with regard to CVD.1 Many researchers have hypothesized that microalbuminuria

is associated with generalized endothelial dysfunction.1 However, which condition precedes the other is

The current consensus among researchers is that somehow, albumin passes through the vascular walls,

and this increased permeability is a marker of endothelial dysfunction.1 Studies in diabetic and

hypertensive patients with microalbuminuria have shown that increased albumin leakage in the

glomerulus is linked to enhanced capillary permeability for albumin in the systemic vasculature.1

Researchers hypothesize that such leakage might lead to hemodynamic strain and instability, which could

then start the atherosclerotic process, and eventually lead to adverse cardiovascular events, such as

congestive heart failure, acute coronary syndromes, myocardial infarction and stroke.4 “Whatever the

mechanism, the evidence linking the presence of microalbuminuria to cardiovascular disease has been well

established in many large studies. In addition to HOPE, there have been the LIFE11 and the PREVEND12

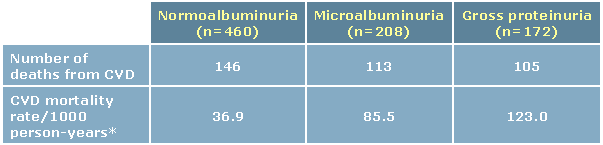

Increased cardiovascular mortality associated with microalbuminuria, as well as gross proteinuria, has also

been established in a population-based study of people with older-onset diabetes (diagnosed after the age

of 30).5 Of the 840 older-onset diabetic persons, 54.8% had normoalbuminuria, while 24.8% had

microalbuminuria and 20.5% had gross proteinuria.5 During the 12-year follow-up, the investigators

identified 364 deaths from CVD, with those individuals who had microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria

having significantly higher risks of cardiovascular mortality (relative risk 1.84 for those with

microalbuminuria, and 2.61 for those with gross proteinuria).5

Microalbuminuria: An increasingly recognized risk factor for CVD Long known to be associated with kidney disease, the importance of protein in the urine is now

becoming recognized as a sensitive, accessible predictor of cardiovascular risk

Microalbuminuria—abnormally high amounts of albumin in the urine— is commonly thought of as an

important risk factor for kidney disease. But recently, studies have emerged highlighting microalbuminuria

as an important, independent marker for endothelial dysfunction and CVD.1-5 Heightened awareness of

microalbuminuria as an early prognostic indicator of CVD risk, knowing when, how, and in whom to screen

for it, and finally, knowing the strategies to manage it, are therefore essential prerequisites for

cardiologists and other healthcare providers.

“We have to acknowledge that microalbuminuria is a new marker for

cardiologists. Nephrologists and diabetologists have traditionally

measured microalbuminuria in their patients to monitor the development

and progression of kidney disease, but now studies such as the HOPE

trial,10 have shown a clear relationship between microalbuminuria and

cardiovascular events. The good news is that we have drugs that can

impact microalbuminuria and have a beneficial effect on the

cardiovascular system,” commented Dr Gilles Montalescot of Pitié-

Defined as an albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 10-25 mg/mmol on the first morning urine sample, or an

albumin excretion rate of 20-200 µg/min on a timed collection,3 microalbuminuria is present in several

populations known to be at risk for CVD, including people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, hypertension,

endothelial dysfunction, and other features of insulin resistance.3

The prevalence of microalbuminuria has been most often studied in patients with diabetes, and large trials

have found the incidence to range between 20% and 40%.1 Studies have also found that approximately

40% of poorly controlled hypertensive individuals have microalbuminuria, and that its prevalence

increases with the duration and severity of hypertension.2 Hypertensive patients who also have

microalbuminuria more frequently have left ventricular hypertrophy, carotid artery thickening, and other

Microalbuminuria can also signify a deleterious cardiovascular prognosis in other individuals, such as

patients with dyslipidemia or the cluster of risk factors that make up cardiometabolic risk, also known as

the metabolic syndrome: abdominal obesity, elevated triglycerides, and elevated fasting blood glucose.2

Although studies have shown that small increases in urinary excretion of albumin predict adverse renal

and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes, hypertension, or both, the exact mechanism of action

is unknown, particularly with regard to CVD.1 Many researchers have hypothesized that microalbuminuria

is associated with generalized endothelial dysfunction.1 However, which condition precedes the other is

The current consensus among researchers is that somehow, albumin passes through the vascular walls,

and this increased permeability is a marker of endothelial dysfunction.1 Studies in diabetic and

hypertensive patients with microalbuminuria have shown that increased albumin leakage in the

glomerulus is linked to enhanced capillary permeability for albumin in the systemic vasculature.1

Researchers hypothesize that such leakage might lead to hemodynamic strain and instability, which could

then start the atherosclerotic process, and eventually lead to adverse cardiovascular events, such as

congestive heart failure, acute coronary syndromes, myocardial infarction and stroke.4 “Whatever the

mechanism, the evidence linking the presence of microalbuminuria to cardiovascular disease has been well

established in many large studies. In addition to HOPE, there have been the LIFE11 and the PREVEND12

Increased cardiovascular mortality associated with microalbuminuria, as well as gross proteinuria, has also

been established in a population-based study of people with older-onset diabetes (diagnosed after the age

of 30).5 Of the 840 older-onset diabetic persons, 54.8% had normoalbuminuria, while 24.8% had

microalbuminuria and 20.5% had gross proteinuria.5 During the 12-year follow-up, the investigators

identified 364 deaths from CVD, with those individuals who had microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria

having significantly higher risks of cardiovascular mortality (relative risk 1.84 for those with

microalbuminuria, and 2.61 for those with gross proteinuria).5

Table 1: Mortality rate according to urine albumin and proteinuria status

*Overall CVD mortality rate: 59.4/1000 person-years Adjusted from Valmadrid et al5

When death from coronary heart disease, stroke, or all causes was used as the study end point, the

increased risks were also significant for both microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria, (1.96 and 2.20,

respectively).5 The investigators concluded that microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria were significantly

associated with subsequent mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and

coronary heart disease, independent of known cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes-related variables.5

It is also well established that microalbuminuria is an adverse prognostic indicator in people with

hypertension.1 In the MONICA study, one of the largest longitudinal studies to investigate a predictive role

of microalbuminuria, hypertensive subjects with albuminuria showed almost a four-fold increased risk of

ischemic heart disease as compared with hypertensive subjects without albuminuria.1

Awareness of the cardiovascular danger posed by microalbuminuria in patients with hypertension and/or

diabetes is the first step in managing these patients; the next is screening for microalbuminuria.

According to the American Diabetes Association, screening for microalbuminuria can be done three ways.

The first is to measure the albumin-to-creatinine ratio in a random spot collection. The second is to do a

24-hour collection with creatinine, allowing the simultaneous measurement of creatinine clearance. The

third is a timed urine collection, either over four hours, or overnight.6 The ADA further advises that the

first method is often the easiest to carry out in an office setting and generally provides accurate

information.6 The first-void urine or other morning collections are best because of diurnal variations in

albumin excretion. However, if this is not possible, different collections in the same individual should be

ADA recommended methods for measuring microalbuminuria

Albumin-to-creatinine ratio in a random spot collection

Timed urine collection over four hours or overnight

Table 1: Mortality rate according to urine albumin and proteinuria status

*Overall CVD mortality rate: 59.4/1000 person-years Adjusted from Valmadrid et al5

When death from coronary heart disease, stroke, or all causes was used as the study end point, the

increased risks were also significant for both microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria, (1.96 and 2.20,

respectively).5 The investigators concluded that microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria were significantly

associated with subsequent mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and

coronary heart disease, independent of known cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes-related variables.5

It is also well established that microalbuminuria is an adverse prognostic indicator in people with

hypertension.1 In the MONICA study, one of the largest longitudinal studies to investigate a predictive role

of microalbuminuria, hypertensive subjects with albuminuria showed almost a four-fold increased risk of

ischemic heart disease as compared with hypertensive subjects without albuminuria.1

Awareness of the cardiovascular danger posed by microalbuminuria in patients with hypertension and/or

diabetes is the first step in managing these patients; the next is screening for microalbuminuria.

According to the American Diabetes Association, screening for microalbuminuria can be done three ways.

The first is to measure the albumin-to-creatinine ratio in a random spot collection. The second is to do a

24-hour collection with creatinine, allowing the simultaneous measurement of creatinine clearance. The

third is a timed urine collection, either over four hours, or overnight.6 The ADA further advises that the

first method is often the easiest to carry out in an office setting and generally provides accurate

information.6 The first-void urine or other morning collections are best because of diurnal variations in

albumin excretion. However, if this is not possible, different collections in the same individual should be

ADA recommended methods for measuring microalbuminuria

Albumin-to-creatinine ratio in a random spot collection

Timed urine collection over four hours or overnight

Factors that can cause transient elevations in urinary albumin excretion include short-term hyperglycemia,

exercise, urinary tract infections, marked hypertension, heart failure, and acute febrile illness.6 The use of

reagent tablets or dipsticks is acceptable, as they show acceptable sensitivity (95%) and specificity (93%)

if done by trained personnel.6 However, reagent strips indicate albumin concentration only and do not

correct for creatinine, as does the random spot collection of the albumin-to-creatinine ratio. If reagent

strips or tablets do indicate that albumin is present in the urine, more specific tests should be used to

“Unfortunately, the reality is that measuring microalbuminuria is often

difficult and time consuming for the busy practitioner,” commented

endocrinologist Dr David CW Lau, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

“Such testing is cumbersome to do for many clinicians, whether in

primary care or specialist settings,” he said.

The dipstick method of measuring albumin in the urine, although

convenient to do in the office, only detects protein excretion that exceeds

300 mg per 24 hours, which is a range that is currently denoted as macroalbuminuria, or gross

proteinuria.1 Nevertheless, this method can be used as an initial screen to determine whether further

“If the dipstick for protein is negative, the next step would be to request a random urine specimen to

measure the albumin-to-creatinine ratio. Of course the gold standard is a 24-hour urine collection for

albumin, or a timed collection over a minimum of four hours, but that is often very difficult to do. In

general, it is a lot easier in the office setting to get a random specimen and ask for an assay for the

albumin-creatinine ratio, which is a very simple test,” he said.

Because of the importance of microalbuminuria as a marker of risk in diabetic and hypertensive

individuals, the Canadian Diabetes Association and the Canadian Hypertension Education Program both

recommend screening for microalbuminuria in such subjects, said Dr Ernesto L Schiffrin, of the Clinical

Research Institute, University of Montreal, Montreal, QC. He suggests that the examination for

microalbuminuria should be performed at least three times within a three-month period in this at-risk

population, and that repeat examinations for microalbuminuria should be

performed in diabetic individuals every six months, and in hypertensive

The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) plays an important

role in modulating the effects of microalbuminuria, noted Schiffrin.

RAAS-directed antihypertensive agents, including both angiotensin-

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), have been demonstrated

to have renoprotective effects, he said.

“Angiotensin II activates the AT1 receptor, thereby resulting in a stimulation of oxidative stress,

inflammatory mediators, proliferation, and other mechanisms that contribute to the progression of renal

disease. It is clear that blockade of the renin-angiotensin system should result in decreased progression of

renal disease in both experimental models and in humans,” Schiffrin added.

Montalescot agrees: “A critical driving factor within both renal and wider cardiovascular pathologies is

overactivation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Agents that delay the progression of renal

disease, therefore, are also likely to be cardioprotective . These agents not only lessen the systemic

consequences of renal dysfunction, but may have other cardioprotective effects by exerting beneficial

effects on endothelia elsewhere in the body and within the heart.”

Endocrinologist Dr Lawrence A Leiter, of St Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto, Toronto, ON,

also acknowledges the importance of the RAAS: “We know that the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

is very important in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. We know that angiotensin II is a

vasoconstrictor and is proatherogenic, and there is now a lot of evidence that drugs which inhibit the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system can have beneficial effects, both in terms of the kidney as well as

Interventions to reduce microalbuminuria

Since endothelial dysfunction occurs early in patients with microalbuminuria, it may be possible to slow or

reverse this dysfunction by modulating microalbuminuria.1 There are several large studies that show such

modulation may have beneficial results, said Leiter.

“We now have evidence that there are a number of interventions that can reduce microalbuminuria and

that can be associated with improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes,” Leiter said, adding:

“Nonpharmacological measures that are well known to improve insulin sensitivity may improve endothelial

function. These include weight loss, exercise, and eating a low-fat diet. Most of the time, however, these

Pharmacological agents such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs have been shown in several landmark

studies to decrease high blood pressure and microalbuminuria.1 Moreover, there is ample evidence to

suggest that specific lowering of microalbuminuria translates into reduced renal and cardiovascular

Factors that can cause transient elevations in urinary albumin excretion include short-term hyperglycemia,

exercise, urinary tract infections, marked hypertension, heart failure, and acute febrile illness.6 The use of

reagent tablets or dipsticks is acceptable, as they show acceptable sensitivity (95%) and specificity (93%)

if done by trained personnel.6 However, reagent strips indicate albumin concentration only and do not

correct for creatinine, as does the random spot collection of the albumin-to-creatinine ratio. If reagent

strips or tablets do indicate that albumin is present in the urine, more specific tests should be used to

“Unfortunately, the reality is that measuring microalbuminuria is often

difficult and time consuming for the busy practitioner,” commented

endocrinologist Dr David CW Lau, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

“Such testing is cumbersome to do for many clinicians, whether in

primary care or specialist settings,” he said.

The dipstick method of measuring albumin in the urine, although

convenient to do in the office, only detects protein excretion that exceeds

300 mg per 24 hours, which is a range that is currently denoted as macroalbuminuria, or gross

proteinuria.1 Nevertheless, this method can be used as an initial screen to determine whether further

“If the dipstick for protein is negative, the next step would be to request a random urine specimen to

measure the albumin-to-creatinine ratio. Of course the gold standard is a 24-hour urine collection for

albumin, or a timed collection over a minimum of four hours, but that is often very difficult to do. In

general, it is a lot easier in the office setting to get a random specimen and ask for an assay for the

albumin-creatinine ratio, which is a very simple test,” he said.

Because of the importance of microalbuminuria as a marker of risk in diabetic and hypertensive

individuals, the Canadian Diabetes Association and the Canadian Hypertension Education Program both

recommend screening for microalbuminuria in such subjects, said Dr Ernesto L Schiffrin, of the Clinical

Research Institute, University of Montreal, Montreal, QC. He suggests that the examination for

microalbuminuria should be performed at least three times within a three-month period in this at-risk

population, and that repeat examinations for microalbuminuria should be

performed in diabetic individuals every six months, and in hypertensive

The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) plays an important

role in modulating the effects of microalbuminuria, noted Schiffrin.

RAAS-directed antihypertensive agents, including both angiotensin-

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), have been demonstrated

to have renoprotective effects, he said.

“Angiotensin II activates the AT1 receptor, thereby resulting in a stimulation of oxidative stress,

inflammatory mediators, proliferation, and other mechanisms that contribute to the progression of renal

disease. It is clear that blockade of the renin-angiotensin system should result in decreased progression of

renal disease in both experimental models and in humans,” Schiffrin added.

Montalescot agrees: “A critical driving factor within both renal and wider cardiovascular pathologies is

overactivation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Agents that delay the progression of renal

disease, therefore, are also likely to be cardioprotective . These agents not only lessen the systemic

consequences of renal dysfunction, but may have other cardioprotective effects by exerting beneficial

effects on endothelia elsewhere in the body and within the heart.”

Endocrinologist Dr Lawrence A Leiter, of St Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto, Toronto, ON,

also acknowledges the importance of the RAAS: “We know that the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

is very important in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. We know that angiotensin II is a

vasoconstrictor and is proatherogenic, and there is now a lot of evidence that drugs which inhibit the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system can have beneficial effects, both in terms of the kidney as well as

Interventions to reduce microalbuminuria

Since endothelial dysfunction occurs early in patients with microalbuminuria, it may be possible to slow or

reverse this dysfunction by modulating microalbuminuria.1 There are several large studies that show such

modulation may have beneficial results, said Leiter.

“We now have evidence that there are a number of interventions that can reduce microalbuminuria and

that can be associated with improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes,” Leiter said, adding:

“Nonpharmacological measures that are well known to improve insulin sensitivity may improve endothelial

function. These include weight loss, exercise, and eating a low-fat diet. Most of the time, however, these

Pharmacological agents such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs have been shown in several landmark

studies to decrease high blood pressure and microalbuminuria.1 Moreover, there is ample evidence to

suggest that specific lowering of microalbuminuria translates into reduced renal and cardiovascular

Indeed, data from two large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, Irbesartan

Microalbuminuria Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Hypertensive Patients (IRMA-2) and the Irbesartan Diabetic

Nephropathy Trial (IDNT), showed that irbesartan was renoprotective and inhibited the development of

overt nephropathy and the progression of renal disease in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes.7

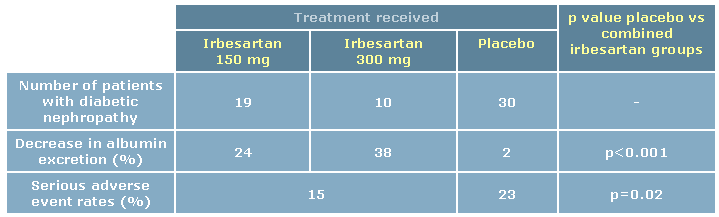

IRMA-2, which was conducted in 96 centres worldwide, randomized 590 hypertensive patients with type 2

diabetes and microalbuminuria but normal kidney function to one of three groups: irbesartan 150 mg

daily, irbesartan 300 mg daily, or placebo. Patients were followed for two years. The primary outcome was

time to onset of diabetic nephropathy, defined as persistent albuminuria in overnight urine specimens,

with a urinary albumin excretion rate >200 µg/min and at least 30% higher than the baseline level.8

During the 24 months of the study, overt nephropathy developed in 30 patients in the placebo group, as

compared with 19 patients in the irbesartan 150 mg group, (p=0.08) and 10 patients in the 300 mg group

Irbesartan reduced the level of urinary albumin excretion throughout the duration of the study. In patients

taking the 150-mg dose, albumin excretion decreased by 24%; in the 300-mg group, albumin excretion

decreased by 38%; whereas in the placebo group, albumin excretion decreased just 2% (p<0.001 for

comparison between placebo and combined irbesartan groups). The higher dose of irbesartan was

significantly more effective in reducing the level of microalbuminuria than the lower dose (p<0.001). In

addition, irbesartan was well tolerated, with more patients on placebo than those receiving irbesartan

reporting serious adverse events (23% for placebo compared with 15% for irbesartan, p=0.02).8

Table 2: Effect of irbesartan vs placebo in the IRMA-2 trial

The IDNT trial, which studied 1715 hypertensive patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes for a

mean duration of 2.6 years, concluded that irbesartan was renoprotective and inhibited the progression of

kidney disease. The patients were randomized to 300 mg of irbesartan daily, 10 mg of the calcium-

channel blocker amlodipine daily, or to placebo. The primary composite end point was time to doubling of

Indeed, data from two large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, Irbesartan

Microalbuminuria Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Hypertensive Patients (IRMA-2) and the Irbesartan Diabetic

Nephropathy Trial (IDNT), showed that irbesartan was renoprotective and inhibited the development of

overt nephropathy and the progression of renal disease in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes.7

IRMA-2, which was conducted in 96 centres worldwide, randomized 590 hypertensive patients with type 2

diabetes and microalbuminuria but normal kidney function to one of three groups: irbesartan 150 mg

daily, irbesartan 300 mg daily, or placebo. Patients were followed for two years. The primary outcome was

time to onset of diabetic nephropathy, defined as persistent albuminuria in overnight urine specimens,

with a urinary albumin excretion rate >200 µg/min and at least 30% higher than the baseline level.8

During the 24 months of the study, overt nephropathy developed in 30 patients in the placebo group, as

compared with 19 patients in the irbesartan 150 mg group, (p=0.08) and 10 patients in the 300 mg group

Irbesartan reduced the level of urinary albumin excretion throughout the duration of the study. In patients

taking the 150-mg dose, albumin excretion decreased by 24%; in the 300-mg group, albumin excretion

decreased by 38%; whereas in the placebo group, albumin excretion decreased just 2% (p<0.001 for

comparison between placebo and combined irbesartan groups). The higher dose of irbesartan was

significantly more effective in reducing the level of microalbuminuria than the lower dose (p<0.001). In

addition, irbesartan was well tolerated, with more patients on placebo than those receiving irbesartan

reporting serious adverse events (23% for placebo compared with 15% for irbesartan, p=0.02).8

Table 2: Effect of irbesartan vs placebo in the IRMA-2 trial

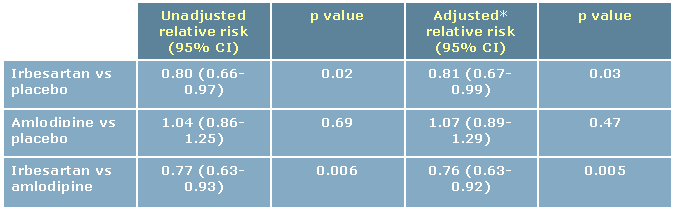

The IDNT trial, which studied 1715 hypertensive patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes for a

mean duration of 2.6 years, concluded that irbesartan was renoprotective and inhibited the progression of

kidney disease. The patients were randomized to 300 mg of irbesartan daily, 10 mg of the calcium-

channel blocker amlodipine daily, or to placebo. The primary composite end point was time to doubling of

the baseline serum creatinine concentration, the development of end-stage renal disease, or death from

The investigators found that treatment with irbesartan was associated with a 20% lower risk of the

primary composite end point compared to placebo, and a 23% lower risk of the primary composite end

point compared to amlodipine. The risk of a doubling of the serum creatinine concentration was 33%

lower in the irbesartan group compared with the placebo group (p=0.003) and 37% lower compared with

patients randomized to amlodipine (p<0.001). Furthermore, irbesartan significantly decreased the risk of

progression to end-stage renal disease by 23% (p=0.07) compared with placebo and amlodipine, and also

lowered the rise of serum creatinine more effectively than the other two treatments.9

Table 3: IDNT: Relative risk of the primary composite end point

*Adjusted for the mean arterial blood pressure during follow-up Adjusted from Lewis et al9

“The IDNT study is perhaps the more important study because it took

patients with type 2 diabetes who had significant proteinuria and showed

that treatment with irbesartan over several years reduced the composite

end point of doubling of serum creatinine, the requirement for dialysis,

The growing awareness of the significance of microalbuminuria in CVD is

an important and positive step towards utilizing this emerging risk

marker in the therapeutic decision-making process. The evidence from large clinical trials attests not only

to the renal but the cardioprotective effects of early recognition and reduction of microalbuminuria. But

perhaps most importantly, the right tools exist to effectively treat patients who present with this early

marker for CVD, thus reducing their CVD risk.

1. Ochodnicky P, Henning RH, van Dokkum RPE, de Zeeuw D. Microalbuminuria and endothelial

dysfunction: Emerging targets for primary prevention of end-organ damage. J Cardiovasc

2. Montalescot G, Collet JP. Preserving cardiac function in the hypertensive patient: Why renal

parameters hold the key. Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:2616-2622.

3. Donnelly R, Yeung JMC, Manning G. Microalbuminuria: A common, independent cardiovascular risk

factor, especially but not exclusively in type 2 diabetes. J Hypertens. 2003; 21(suppl 1): S7-S12.

4. Naidoo DP. The link between microalbuminuria, endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease

in diabetes. Cardiovasc J South Afr. 2002; 13:194-199.

5. Valmadrid CT, Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BEK. The risk of cardiovascular disease mortality associated

with microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria in persons with older-onset diabetes mellitus. Arch

6. American Diabetes Association. Nephropathy in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004; 27:S79-S80.

7. Croom KF, Curran MP, Goa KL, Perry CM. Irbesartan: A review of its use in hypertension and in the

management of diabetic nephropathy. Drugs 2004; 64:999-1028.

8. Parving HH, Lehnert H, Mortensen JB, et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic

nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:870-878.

9. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin receptor

antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;

10. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril,

on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients: The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study

Investigators. N Eng J Med. 2000; 342:145-53.

11. Wachtell K, Ibsen H, Olsen MH, et al. Albuminuria and cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients

with left ventricular hypertrophy: The LIFE study. Ann Intern Med. 2003; 139:901-906.

12. Hillege HL, Janssen WM, Bak AA, et al. Microalbuminuria is common, also in a nondiabetic,

nonhypertensive population, and an independent indicator of cardiovascular risk factors and

cardiovascular morbidity. J Intern Med. 2001; 249:519-526.

13. Diercks GFH, van Boven AJ, Hillege HL, et al. Microalbuminuria is independently associated with

ischemic electrocardiographic abnormalities in a large non-diabetic population. The PREVEND

(Prevention of Renal and Vascular ENdstage Disease) study. Eur Heart J. 2000; 21:1922-1927.

the baseline serum creatinine concentration, the development of end-stage renal disease, or death from

The investigators found that treatment with irbesartan was associated with a 20% lower risk of the

primary composite end point compared to placebo, and a 23% lower risk of the primary composite end

point compared to amlodipine. The risk of a doubling of the serum creatinine concentration was 33%

lower in the irbesartan group compared with the placebo group (p=0.003) and 37% lower compared with

patients randomized to amlodipine (p<0.001). Furthermore, irbesartan significantly decreased the risk of

progression to end-stage renal disease by 23% (p=0.07) compared with placebo and amlodipine, and also

lowered the rise of serum creatinine more effectively than the other two treatments.9

Table 3: IDNT: Relative risk of the primary composite end point

*Adjusted for the mean arterial blood pressure during follow-up Adjusted from Lewis et al9

“The IDNT study is perhaps the more important study because it took

patients with type 2 diabetes who had significant proteinuria and showed

that treatment with irbesartan over several years reduced the composite

end point of doubling of serum creatinine, the requirement for dialysis,

The growing awareness of the significance of microalbuminuria in CVD is

an important and positive step towards utilizing this emerging risk

marker in the therapeutic decision-making process. The evidence from large clinical trials attests not only

to the renal but the cardioprotective effects of early recognition and reduction of microalbuminuria. But

perhaps most importantly, the right tools exist to effectively treat patients who present with this early

marker for CVD, thus reducing their CVD risk.

1. Ochodnicky P, Henning RH, van Dokkum RPE, de Zeeuw D. Microalbuminuria and endothelial

dysfunction: Emerging targets for primary prevention of end-organ damage. J Cardiovasc

2. Montalescot G, Collet JP. Preserving cardiac function in the hypertensive patient: Why renal

parameters hold the key. Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:2616-2622.

3. Donnelly R, Yeung JMC, Manning G. Microalbuminuria: A common, independent cardiovascular risk

factor, especially but not exclusively in type 2 diabetes. J Hypertens. 2003; 21(suppl 1): S7-S12.

4. Naidoo DP. The link between microalbuminuria, endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease

in diabetes. Cardiovasc J South Afr. 2002; 13:194-199.

5. Valmadrid CT, Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BEK. The risk of cardiovascular disease mortality associated

with microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria in persons with older-onset diabetes mellitus. Arch

6. American Diabetes Association. Nephropathy in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004; 27:S79-S80.

7. Croom KF, Curran MP, Goa KL, Perry CM. Irbesartan: A review of its use in hypertension and in the

management of diabetic nephropathy. Drugs 2004; 64:999-1028.

8. Parving HH, Lehnert H, Mortensen JB, et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic

nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:870-878.

9. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin receptor

antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;

10. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril,

on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients: The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study

Investigators. N Eng J Med. 2000; 342:145-53.

11. Wachtell K, Ibsen H, Olsen MH, et al. Albuminuria and cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients

with left ventricular hypertrophy: The LIFE study. Ann Intern Med. 2003; 139:901-906.

12. Hillege HL, Janssen WM, Bak AA, et al. Microalbuminuria is common, also in a nondiabetic,

nonhypertensive population, and an independent indicator of cardiovascular risk factors and

cardiovascular morbidity. J Intern Med. 2001; 249:519-526.

13. Diercks GFH, van Boven AJ, Hillege HL, et al. Microalbuminuria is independently associated with

ischemic electrocardiographic abnormalities in a large non-diabetic population. The PREVEND

(Prevention of Renal and Vascular ENdstage Disease) study. Eur Heart J. 2000; 21:1922-1927.

Source: http://www.medscape.com/files/editorial/articles/548420/SAV-06-0455.pdf

Calanka Madow Sheekh DR Cismaan Macalim Maxamud ﻥﺃ ﺪﻬﺷﺃﻭ ,ﻪﻟ ﻚﻳﺮﺷ ﻻ ﻩﺪﺣﻭ ﷲﺍ ﻻﺇ ﻪﻟﺇ ﻻﺃ ﺪﻬﺷﺃﻭ ﹰﺎ , ﻛﺭﺎﺒﻣ ﹰﺎﺒﻴﻃ ﹰﺍﲑﺜﻛ ﹰﺍﺪﲪ ﷲ ﺪﻤﳊﺍ ﺪﻌﺑ ﺎﻣﺃ ,ﻢﻠﺳﻭ ﻪﻴﻠﻋ ﷲﺍ ﻰﻠﺻ ﻪﻟﻮﺳﺭﻭ ﻩﺪﺒﻋ ﹰﺍﺪﻤﳏ Horu Dhac Diyaariyaha

Diabetes Youth New Zealand PO Box 67 – 041 Mt Eden Auckland Natalie Davis Therapeutic Group Manager PHARMAC PO Box 10 254 Wellington 6143 Diabetes Youth New Zealand (DYNZ) represents children and young people up to the age of 18 years and their families living with diabetes. DYNZ is closely affiliated with Diabetes New Zealand, and the DYNZ President sits on the DNZ National Board. At pre